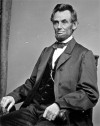

I recently saw Lincoln, Steven Spielberg’s historical drama garnering so much attention for its Oscar buzz and Daniel Day Lewis’ universally-acclaimed performance as America’s sixteenth president.

I am neither a movie critic nor film connoisseur, so I will make no attempt to offer anything akin to criticism. I simply wish to draw a brief comparison to the novel upon which Lincoln is, in part, based. Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals is as good as everyone says it is. Painstakingly researched, jam-packed with rich historical detail, and written with an urgency and dramatic flair that rivals Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, it’s a must-read. It’s a must-read for any lover of history, or really, any lover of human nature.

I am neither a movie critic nor film connoisseur, so I will make no attempt to offer anything akin to criticism. I simply wish to draw a brief comparison to the novel upon which Lincoln is, in part, based. Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals is as good as everyone says it is. Painstakingly researched, jam-packed with rich historical detail, and written with an urgency and dramatic flair that rivals Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, it’s a must-read. It’s a must-read for any lover of history, or really, any lover of human nature.

Spielberg’s film focuses on this American hero through the lens of the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, the Constitutional addition that outlawed slavery.

Kearns Goodwin covers more ground. She covers more years and a larger number of the personal and public battles which Lincoln waged. What I realized while reading Team of Rivals was that President Lincoln was super-human in his ability to forgive those by whom he had been wronged; an essential character trait, albeit a rare one, when trying to win half of the country back to your side after its secession. But Lincoln was good on both a macro and a micro scale. Some of his more impressive displays of altruism, I thought, occurred on the smaller stage of his private daily life. A smaller stage, and yet perhaps a more difficult one on which to cede your own right to being right.

Lincoln was dealt with a seemingly endless series of setbacks during his too-brief time on earth. Time and again, Lincoln proved willing to meet vindictive or petty rivals (and friends) with magnanimity. Kearns Goodwin describes the undercutting that happened within his own cabinet: the time his own Treasury Secretary tried to run against him and thwart Lincoln’s re-election; the time his top General, George McClellan, tried to take his boss’ job. And the personal heartbreak he faced is difficult to imagine: losing his mother at a young age, losing the first love of his life, burying two of his four sons, and struggling with a wife who was mentally unstable. Lincoln is justifiably understood to be one of the best, if not the best, leaders our country has known. But he was more than that – he was a truly good, decent man.

On the macro level, his steady leadership and vision were what the nation needed through years of Civil War. Kearns Goodwin and Spielberg both illuminate this fact: the Civil War could have gone any number of ways. Victory for the Union was far from a sure thing; peace and reconciliation were one option, but a large number of disastrous outcomes were not only possible, but probable. Slavery might have been addressed, or not addressed, via political and legislative approaches very different from Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment. It was Lincoln who brought about the end of slavery and the peaceful resolution of the Civil War, not because of the hand he was dealt, but in spite of the hand he was dealt.